Welcome to

St. Anselm’s Abbey

A Benedictine Monastery

in the Heart of Washington, DC

Pray With Us

We invite you to join us for any of our daily liturgies here at St. Anselm’s Abbey. If you cannot come in person, daily Mass and occasional Vespers can be streamed online.

“

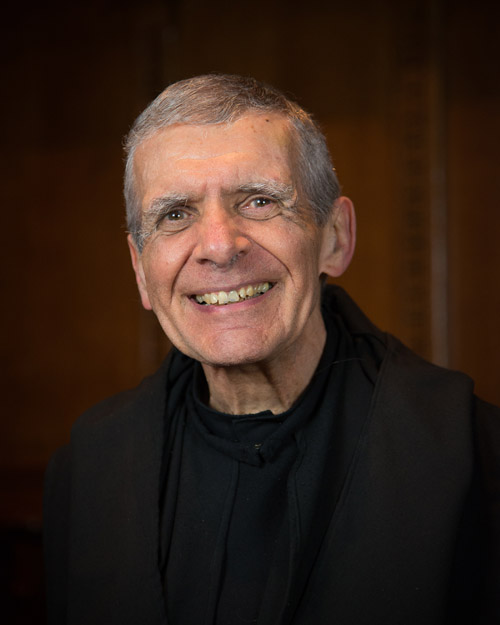

Rt. Rev. Dom James Wiseman, OSB

Abbot of St. Anselm’s Abbey

Near the north-east boundary of the District of Columbia, twelve minutes by Metro from Union Station and twenty minutes from the Capitol, is a thriving Benedictine monastery. Here, we monks live the life of prayer established by our sixth-century founder St. Benedict and where we continue that life and the aspirations of our founder for the glory of God and the sanctification of our nation and world.

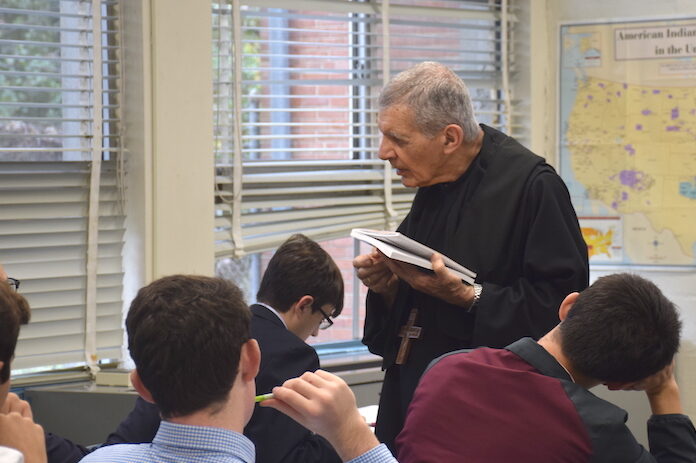

Within an urban oasis of 40 acres of secluded woodland surrounding the monastery, the usual sounds of a busy city are subdued. Here, too, stands our highly regarded middle school and high school, where the values of our patrons, St. Benedict and St. Anselm, are proclaimed among our youth as we prepare them for lives of service to God and their fellow human beings.

Some have referred to the abbey as “Washington’s best kept secret”; perhaps this is because monks are not naturally given to the more ostentatious ways of projecting themselves upon the surrounding world. Monasteries are primarily places of prayer and virtuous activity, and our evangelization is precisely through prayer, spiritual direction, and education. We cordially invite you to share our secret. We invite you to “come and see.”

Connect with Us

You are invited to join the St. Anselm’s community in a variety of ways.

We encourage you to explore our website, starting with the avenues below.

Liturgy & Events

We invite you to join us for liturgy or another event in person or online.

Guests

We encourage you to submit a guest reservation request to visit the abbey.

Vocations

You are invited to explore the process of pursuing a vocation at St. Anselm’s.

Oblates

Get information about our lay oblate community and its monthly meetings.

Recent News at the Abbey

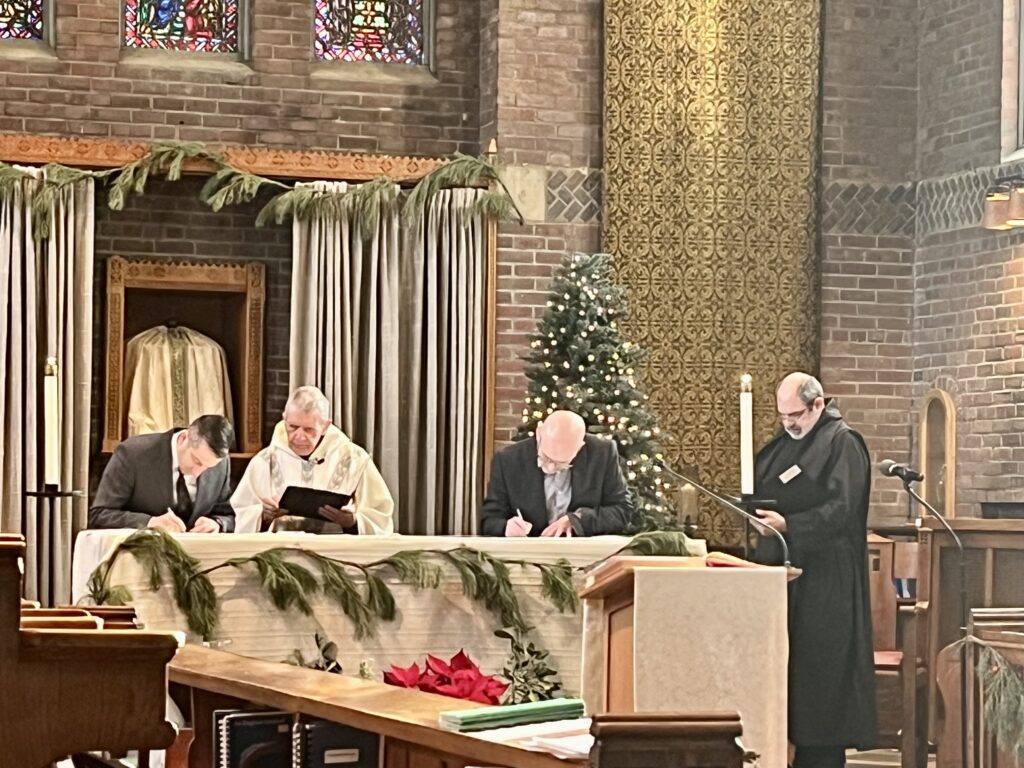

Enrollment of Two Oblate Novices

At our March oblate meeting, Father Ignacio conducted an Enrollment ceremony for our two new Novices, Jennifer Chalmers and Teresa…

Clothing of Br. Maximilian

On February 29, 2024, John Castonguay was clothed as a novice of our community. He will spend the next year…

Oblate Retreat

Our annual retreat, with the theme “Islands of Silence”, was an opportunity for our oblates to gather and to step…

OUR LIFE

Monastic Life at St. Anselm’s

All members of the community at St Anselm’s are involved in prayer and work, and share in the common life of the community.

Prayer

PRAYER is undertaken by the whole community together early in the morning, at midday, in the early evening and at night.

Work

WORK is necessary for a balanced life, according to the Rule, since “idleness is the enemy of the soul”. As in any household there are tasks to be done by individual members for the good of all.

Community Life

COMMUNITY LIFE includes prayer and work, for even prayer undertaken individually is a contribution to the life of the monastery and the work of each monk contributes to the well-being of the whole community.